Duck and Cover: Cold War Caving

- Madison Holt

- Jan 8

- 11 min read

This is part two of the Duck and Cover series. Read Duck and Cover: The 1961 Fallout Shelter Boom to learn about personal fallout shelters in Springfield, Missouri.

At the height of the Cold War, many Americans had their eyes on the skies, watching for incoming nuclear missiles from the Soviet Union and wondering what they would do if diplomacy failed the United States. Some found answers beneath their feet.

When federal efforts to survey and designate community fallout shelters stalled in 1961, some civilians took matters into their own hands. In the Ozarks, keeping up with the Joneses meant buying or building your very own fallout shelter.

The rush underground was so widespread that in September of 1961, the Sunday News and Leader ran a two-page article detailing the luxuries one could find in pre-made and custom fallout shelters. But what about those who couldn’t afford a backyard shelter? Were they supposed to perish in a nuclear disaster because their neighbors wouldn’t include them in an emergency plan? Did families with shelters have a responsibility to account for people outside of their household?

Taking Shelter

By the end of 1962, Congress had finally approved funds to stock provisions in community fallout shelters, and the focus shifted from private bunkers to public shelters. The first designated community shelter in Greene County was the basement of the City Utilities building, which was marked with a striking yellow-and-black shelter sign in December 1962. However, more community shelters were needed.

In October 1965, the Greene County Office of Civil Defense was working with Civil Defense officials from Denver to identify, license, and stock potential community fallout shelters in and around Springfield. If officials could identify enough community shelters to shield a majority of the local population, then they would receive federal funding for a comprehensive Community Shelter Plan that would help determine capacity and evacuation routes for each location. In the search for suitable shelters, these Civil Defense officials cast their gaze beneath the city.

The Ozarks’ unique geology put the region at an advantage in the case of nuclear war, with natural caves putting several feet of earth between radioactive fallout and those sheltering within. Griesemer Quarry (now known as the Springfield Underground), Fantastic Caverns, Crystal Cave, and Doling Park Cave had previously been flagged as potential community shelters for Greene County residents. According to Greene County Civil Defense Director Don Bown, these four sites could together provide protection for 48,882 people.

Three days into their survey, Civil Defense officials had designated 23 locations as community shelters. Fantastic Caverns was approved to hold 1,030 people and was stocked with supplies. Crystal Cave and Doling Park Cave were not initially approved, however, and the status of Griesemer Quarry was left unclear, being neither approved nor explicitly ruled out as a potential community shelter.

The result of these efforts was the “City of Springfield & Greene County, Missouri Community Shelter Plan.” Published and distributed in February 1970, the Community Shelter Plan listed nearly 200 existing structures as community shelters, outlined how residents could reach their designated shelter, and detailed what provisions they should bring along in case of an emergency. Griesemer Quarry, Fantastic Caverns, Doling Park Cave, and Crystal Cave were all listed as community shelters. Both Griesemer Quarry and Fantastic Caverns would go on to hold a unique place in local Cold War history.

What would your shelter have been?

Find the number closest to your home or workplace:

Match the number to the shelter list:

Griesemer Quarry

Excavations began in Griesemer Quarry at the intersection of Route 66 and the Frisco Railroad in 1946. Joseph J. Griesemer started the limestone mining operation under his name, and it’s been a family operation ever since. In 1954, enough limestone had been removed from the quarry to allow a “room and pillar” method of mining. Rather than extracting as much limestone as possible, Griesemer left 30-foot-wide pillars in place. These pillars support the 50-foot thick ceiling above, creating spacious underground rooms. By 1960, developers were building the first warehouses in these massive subterranean spaces. Today, the industrial park is known as the Springfield Underground.

Griesemer Quarry was evaluated for its potential as a community shelter in October of 1965, but no decision was made at that time. A 1970 article in the Springfield Leader and Press suggests that officials may have hesitated to designate Griesemer Quarry as a community shelter due to its relatively remote location. In their preparations, Civil Defense officials assumed a scenario wherein the residents of Springfield would walk to their designated community shelter rather than drive. Of the 47,165 people that Griesemer Quarry could accommodate, officials estimated that only 15,900 would feasibly walk there within an hour. This logistical concern may have delayed approval of Griesemer Quarry as a community fallout shelter.

Nevertheless, when the Community Shelter Plan was distributed as a newspaper supplement in February 1970, Griesemer Quarry was included as a community fallout shelter, alongside Fantastic Caverns, Doling Park Cave, Crystal Cave, and nearly 200 other structures in Greene County.

While doomsday preparations were occurring above, business continued below as usual. Companies used Griesemer Quarry’s underground warehouses to store a variety of goods, including consumer appliances, produce, and raw cheese (a fact which would later fuel urban legends about the “Cheese Caves,” a hidden cache of government cheese stored in the Springfield Underground).

Fantastic Caverns

The cave now known as Fantastic Caverns was discovered to the north of Springfield by farmer John Knox and his dog in 1862. Knox kept the cavern a secret to prevent soldiers from either side of the Civil War from disturbing it. Knox opened the cave to the public on February 14, 1867, and two weeks later, twelve women from the Springfield Women’s Athletic Club braved the cold and explored the cave. Equipped with ladders and carbide lamps, these women wrote their names on the cave wall, cementing their place as the first recorded explorers of the cavern.

During Prohibition, the cave was used as a speakeasy. Later, gas (and then electric) lights were installed, and the cavern was opened for tours as one of Missouri’s many show caves. When the cave stopped making money as a tourist attraction, it was sold to the Ku Klux Klan. Fortunately, this dark chapter in the cavern’s history was short-lived, as the terrorist group was unable to afford mortgage payments on the cave and sold it in 1930. In 1941, the cavern was reopened as a show cave.

In 1951, the cave was renamed Fantastic Caverns. The new name attracted tourists as well as music lovers: The cavern’s Auditorium Room played host to concerts throughout the 1950s and 1960s, which were broadcast under the name "Farmarama" on the local radio station KGBX. The popularity of these concerts was ultimately to the cave’s detriment, as it began to sustain damage from such frequent and heavy use. As such, the concerts were discontinued.

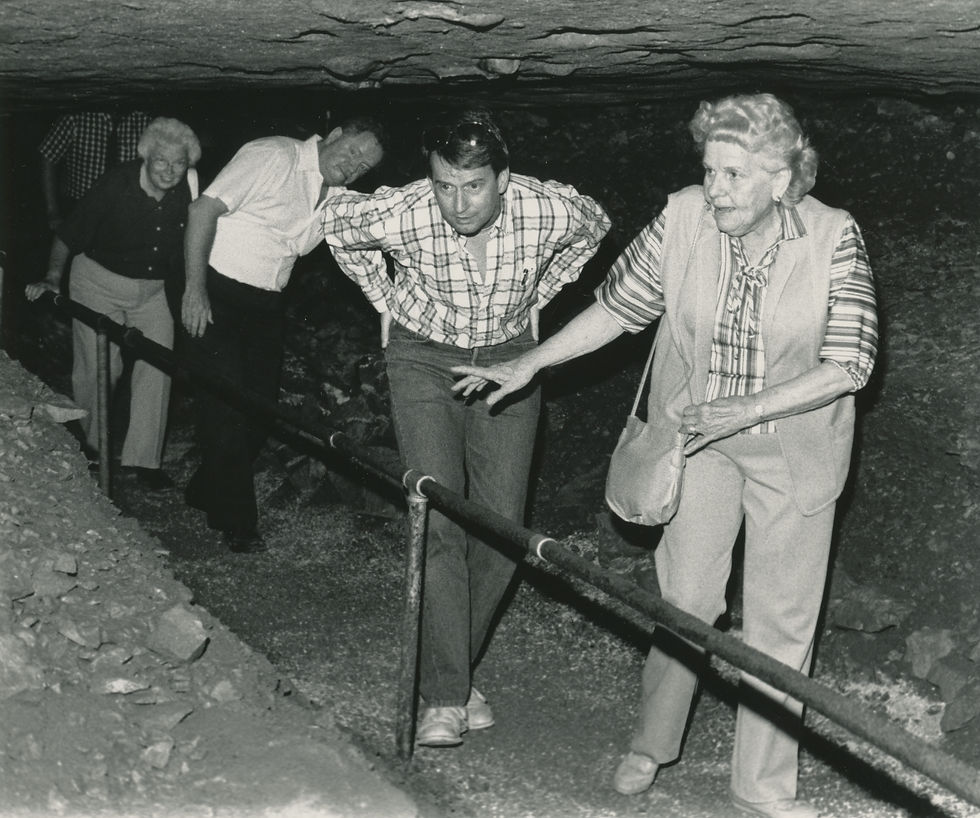

The Air Force approached the Missouri Speleological Survey in 1961 for information on caves throughout southern Missouri. After visiting Fantastic Caverns, they found that its large underground rooms had the potential to shelter Air Force personnel and their dependents in case of a nuclear attack. With several cavernous chambers, an air supply that recycles itself once daily, a consistently cool temperature, and clean water, Fantastic Caverns seemed like an ideal place to wait for radioactive fallout to dissipate. Captain Mark Trimble, a weather officer of the Air Force Reserve Recovery Squadron, was credited with arranging the trip.

Captain Mark Trimble and his mother, Mary Trimble, had purchased Fantastic Caverns in May 1961, only six months before the Air Force survey. Having previously developed the Shepherd of the Hills attraction in Branson, the Trimble family had already made their name in Ozarks tourism. Using a tram pulled by butane-fueled Jeeps, the new format made the cave accessible to people who wouldn’t be able to explore it on foot.

Following the inclusion of Fantastic Caverns in the Community Shelter Plan, Civil Defense officials sought to test the practicality of the show cave as a fallout shelter. On August 8, 1971, a call for volunteers willing to participate in a simulation of shelter living was published in the Springfield Leader and Press. As it turned out, this simulation would be no walk in the park (or a tram ride through a cave).

Participants were told ahead of time that their rations would include “six single or three double [high protein] crackers and one cup of water, issued six times daily, prorated Friday and Saturday.” Volunteers were instructed to bring prescription medicines, snacks, toiletries, bedding, sleeping bags, as well as games, books, and toys for entertainment. Pets, weapons, alcoholic beverages, and gambling equipment were among the items prohibited. The agenda included simulations of activities that would be necessary during a real nuclear attack, such as monitoring radiation levels, treating mild radiation sickness, and establishing communications with the outside world. Tours were to continue during the experiment, skirting the simulation area to allow visitors a glimpse at the shelter exercise.

While 75 people signed up for the simulation, only 48 arrived on August 27 to take on the challenge. Leader and Press staff writer Warren Guerin’s review of the Fantastic Caverns exercise paints a picture of community shelter living that is starkly different from that of the family shelter drills of 1960 and 1961.

Despite the briefing letter that went out to volunteers before the exercise, participants were, according to Guerin, “unready… in that they didn’t know what to expect during the two days of simulated nuclear attack and radioactive fallout conditions; and uneducated as to what was expected of them as individuals forced to live together for their own protection,” although Guerin did concede that in a real nuclear situation, no one would be ready. To that end, he suggested that everyone undertake any shelter management training available to them. Guerin also advises that shelter managers should “present a thorough, low-keyed, well informed talk to shelter residents.”

According to Guerin, even the three shelter officers were unprepared to manage the volunteers or undertake “simulated nuclear activities.” Indeed, the emergency activities seem to have fallen by the wayside, with Guerin noting that “a lot of the time, it seemed like there was nothing to do… Some girls managed to come up with a rope and began skipping rope Saturday afternoon, but the noise echoing through the cave distracted the tour operators and they had to tone it down and then finally quit.” The adults occupied themselves with a Frisbee tournament, which became just as boisterous as the jump rope, and had to stop as well.

Cold War Cooldown

Today, there is no readily accessible map of current community fallout shelters for Springfield and Greene County. The 1970 Community Shelter Plan was only recently discovered because the Springfield News-Leader had kept it among other documents for years before donating the items to the Springfield–Greene County Library. Local History & Genealogy staff found it by chance before this article was published.

Then again, a lot has changed since the Community Shelter Plan’s publication. The threat of nuclear war has diminished due to multiple factors. Advances in missile defense, improved satellite detection, and an emphasis on deterrence have done much to ease nuclear anxieties. The Federal Emergency Management Agency, created in 1979 to bolster nuclear disaster preparedness, has since shifted its focus to comprehensive emergency management.

While FEMA does update its guidance on responses to nuclear detonations, this advice is written for emergency managers, public health planners, and mass care providers. These are not the Do-It-Yourself fallout shelter booklets of the 1960s.

In any case, the best way to prepare for an emergency is to have a plan in place. Knowing what to do ahead of time could save your life. The key to avoiding radioactive fallout in the event of a nuclear detonation is to put as much material between yourself and the outdoors. Underground spaces and interior rooms away from windows offer significant fallout protection.

During the Cold War, civilians in the Ozarks initially relied on homemade or store-bought solutions to the threat of nuclear war, displaying their values of thrift and ingenuity. Many of these shelters have stood the test of time as tornado shelters or underground pantries. Later, the people of the Ozarks turned to their communities as Civil Defense officials worked to plan for the worst. In the process, locals gained an appreciation for the unique geology of the Ozarks and for the robust cave systems beneath their feet. Luckily, our personal and community shelters were never put to the test, but the people of the Ozarks were about as ready as anyone.

Want more local history news and stories delivered directly to your inbox? Sign up for Local History & Genealogy's newsletter and email announcements.

Special Acknowledgement

Special thanks to John Griesemer for providing additional information on the history of Griesemer Quarry and the Springfield Underground.

Resources

"23 More Buildings Okayed, To Shelter 7521 Persons." Springfield Daily News, 29 Oct. 1965, p. 39.

"CD to Open Drive to Pinpoint, Stock County Fallout Shelters." Springfield Leader and Press, 18 Oct. 1965, p. 17.

"CD Seeking Volunteers." Sunday News and Leader, 8 Aug. 1971, pp. A21–24.

"Fantastic Caverns Sale Is Announced." Springfield Leader and Press, 26 May 1961, p. 11.

Federal Emergency Management Agency. Planning Guidance for Response to a Nuclear Detonation. 3rd ed., 2022.

Greene County (Mo.) Office of Civilian Defense. City of Springfield & Greene County, Missouri Community Shelter Plan. 1970, Springfield-Greene County Library, Springfield News-Leader Collection.

Guerin, Warren. "Should Fill Empty Hours." Springfield Leader and Press, 14 Sept. 1971, p. 13.

"Ozarks Cave For Shelter?" Sunday News and Leader, 12 Nov. 1961, p. A17.

"See County Shelter Need." Springfield Leader and Press, 6 Jan. 1970, p. 14.

Springfield Underground. "From Rocks to Real Estate." Springfield Underground.

United States Office of Civil Defense, Family Shelter Designs. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1962.

Wood, Larry. "A History of Fantastic Caverns." The Ozarks Mountaineer, vol. 54, no. 3, June 2006, pp. 9–12.

Further Reading

Center for Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies. "Cold War in the Heartland." University of Kansas.

Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign Records (S0454). The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center–St. Louis.

Schlosser, Eric. Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety. Penguin Press, 2013.

Sigel, Gary L. Missouri at Ground Zero: What Nuclear War Would Do to One State. Institute of Applied Research, 1982.

Weaver, H. Dwight. Missouri Caves in History and Legend. University of Missouri Press, 2008.